A friend of mine, Jack Jennings, who served with the 1st battalion Cambridgeshires in Singapore and helped build the very same bridge featured in the movie, passed away last year aged 104. He was the last of the ‘Fen Tigers ‘and his ‘mouthy’ playing and storytelling is sorely missed. I had the privilege of sharing a train ride with him across the Wampo Viaduct in Thailand a few years back. We sat talking about everything and anything other than the war; Thai food, the mountains and the heat; a relatively normal conversation as the train chugged along the railway he had helped to build 70 odd years previously. Eventually he leant over to me and so as not to be heard by our fellow passengers said, ‘Should we tell them?’ nodding at the commuters.

‘Tell them what Jack?’ I asked.

‘We only put a 50 year warranty on our work!’

What stories he could tell!

Somehow, like Jack’s warning about the longevity of his and his mates’ handiwork, it’s our job, if not our duty, to hand down this history to the next generation. The only proviso being we cannot expect them to understand why we are whistling ‘Colonel Bogey’ as we enter the room.

I continued the talk with the slides prefixed with a warning that what we are discussing might get a little bit nasty. Certainly, there were a few gulps when the conversation turned to scrotal dermatitis, beri-beri and how to clear out a leg ulcer with a rusty spoon. We discussed the reasons behind the construction of the railway and the ‘living’ conditions the POWs faced. But somehow it didn’t quite sink home. Until the last slide which showed the grave of one of our former pupils at Kanchanaburi.

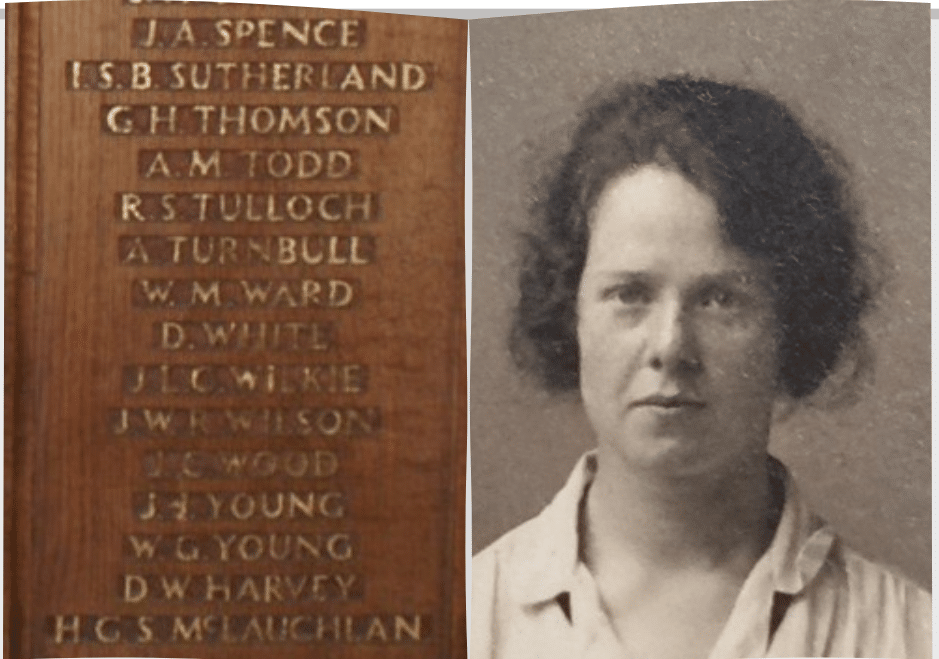

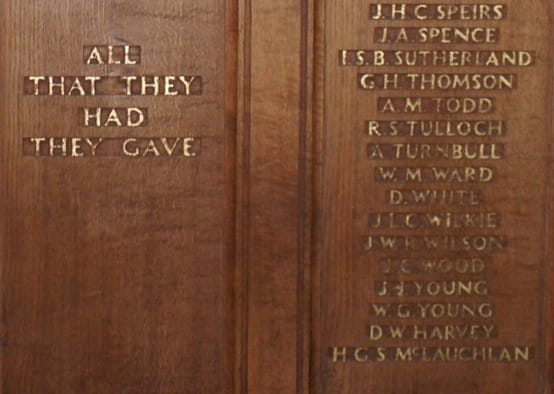

If you go along to the remembrance wall outside the library at the Old College, you’ll see a list of names written in gold leaf on the wooden panel detailing those former pupils of Daniel Stewart’s College who died in World War 2. The two lists sitting under the school crest are set out like soldiers on parade, nice straight columns and in alphabetical order, until you reach the bottom when suddenly the names seem to be listed somewhat randomly. Among those last names is that of David Warner Harvey.

David was born in Midlothian in 1910 and attended Daniel Stewart’s, graduating in the class of 1929. He went on to Edinburgh University to attain a BSC in Forestry Management before seeking his fortune out in the Far East as a plantation manager. He worked for a company called Bradwell FMS Rubber Estates ltd and as was common for the age, he joined the local volunteer unit putting his skills to good use as an engineer. When the war broke out, he was transferred to the Federated Malay States Volunteer Force (FMSVF) and fought in the Malayan campaign against the invading Japanese armies. He was finally captured at the fall of Singapore on 15th February 1942 and was transferred, like many, to the Changi prison of war camp. From there, he was sent with F force on the 28th of April 1943 to Ban Pong in Thailand, the camp which marked the southern end of the ‘Death Railway’. Then he was moved with his colleagues to various work camps along the length of the construction, enduring the harshest of conditions throughout what is known as the ‘Speedo’ period, where the Japanese drove the POW workforce as hard as they could to ensure the completion of the project before the end of the year. David almost made it. According to roll books held in Changi, he died in Kanchanaburi hospital on 13th December 1943, after falling sick with dysentery and Beri-Beri. A terrible way to go and so far from the corridors of our school where his name can be found today.

So why the mix up on the memorial? Well, this is what makes the story of the Far East POWs so tragic. By the end of 1945 and early 1946 when many of the prisoners returned to the United Kingdom, their arrival was no longer newsworthy. The previous months had seen the return of many POWs from Europe and the elation had somewhat diminished after the initial rush. So much so, that the story of the Thai Burma Railway and the treatment of prisoners out in the Far East was never really spoken about. To make matters worse, it was government policy at the time to advise all prisoners not to talk about their experiences to their family and friends so as not to worry them. Bottling it all up simply increased PTSD and encouraged legends rather than facts. It was not until the ‘Bridge on the River Kwai’ movie in 1959, that the people back home began to understand what these survivors had gone through. David’s name appears at the bottom of the list because the school had not been advised of his death at the time the memorial was created. It took months for the authorities to confirm the demise of the men on the Railway, lost as they were in countless graveyards up and down the jungle tracks. Only then was the school memorial taken down off the wall and his name was carefully added.

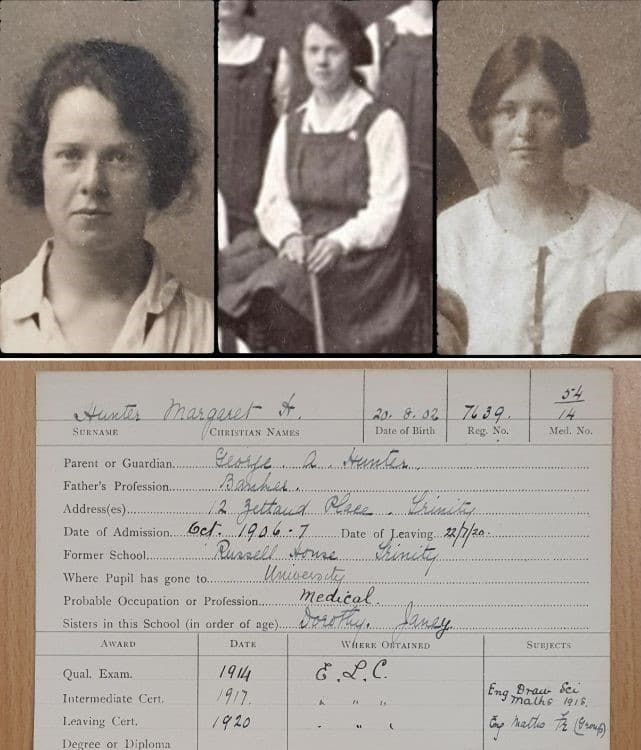

David was not the only former pupil who experienced captivity at the hands of the Japanese during World War 2. You may recall the series ‘Tenko ‘on BBC during the 1970’s. It followed the experiences of women and children who had been unable to escape from Singapore and Java before it was occupied. Among the main characters was the doctor played by Stephanie Cole, who proved to be the stalwart of the camp, not only providing medical help for all the patients but also maintaining discipline and morale in the darkest of times. It is thought that this character was based on Dr Margaret Thomson, (nee Hunter), who had travelled out to the Far East with her husband and had kept a practice in Malaya prior to hostilities.

Margaret had fled to Singapore when the invasion reached her neighbourhood and spent sometime helping in the hospitals there before boarding one of the last ships out. The SS Kuala made it to the other side of the Straits of Malacca before being spotted by Japanese aircraft and bombed. The passengers and crew took to the water and Margaret herself suffered a severe wound to the buttocks from shell fragments. She clung desperately to a mattress but refused to get into the first rescue boat to find her as there were more seriously wounded passengers in the vicinity. Later, on the beach where they were unloaded and despite her wounds she helped look after the most seriously wounded survivors. Eventually they moved inland and were later picked up by the Japanese who transferred them into the first of many internment camps. Margaret survived two and a half years of captivity in some horrendous conditions, but like her character betrayed on TV, she remained resolute, defiant and brave until her release. Her husband also survived his POW ordeal after he was picked up in Singapore and transferred onto the Railway. Both returned to Scotland to live out their lives together in peace. Margaret received an MBE ‘in absentia’ in 1943 for her exploits in the Far East.

Suffice to say Margaret Hunter attended Edinburgh Ladies College and graduated in the class of 1920. She studied medicine at the University of Edinburgh before marrying and moving to Carey Island in Selangor. For many years researchers were unable to find a photograph of Margaret because she never sought the limelight and kept her war experiences to herself. Recently a newspaper article was discovered with a very grainy picture of Margaret in it. I’m happy to say research undertaken by our Young Historians at MES has not only unearthed more information about this story but also found four different portraits of Margaret, as she was captain of the 1st XI hockey team in 1920! ‘Mitis et Fortis’ seems the most fitting epitaph for such an incredible woman.

Singapore is 6,792 miles away from Edinburgh, the average temperature is 24°C, reaching 30°C plus in the height of summer. It takes 15 hours by aircraft to fly there and is an incredible city to live in. If it seems such a long way from Ravelston and Old College today, imagine travelling there in 1942 and what it must have been like for those former pupils of our schools to take the decision to head out to the Far East to start a new life. And take a moment to think about their wartime stories, hidden histories which have long been overlooked, but can now be found in our school archives and on the very walls of our buildings and memorials.

by Jon Cooper, Heritage Officer, ESMS